My Narrative Journalism Class wrote a series of longform profiles of the various plaintiffs, experts and lawyers involved in a toxic tort case in the Bronx that took 22 years to settle. The full website with all the stories can be found here.

My article focused on the plaintiffs’ expert witnesses – their experiences and the debate over the science at the heart of the case. I’ve included it below, though I highly encourage everyone to visit the full site and read my classmates’ stories for a more complete understanding of this case. I took the lead on creating the page for these stories, and made all the graphics in Photoshop.

The Elusive Truth

Expert witnesses and the debate over causation

Dr. Richard Neugebauer, an epidemiologist and professor at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, immediately comes across as an amiable and intellectual scientist. Though he spends a good deal of time teaching classes at Columbia’s medical campus, he has an accomplished resume that spans the globe.

Neugebauer was in Rwanda for most of the fall and winter of 1997 working to evaluate a UNICEF program helping children with the emotional trauma they endured after seeing violence and genocide – an experience he said “put into perspective everything else in my life.” He has revisited the subject twice since in prestigious epidemiological journals. He has also studied mental health issues in Uganda, and has on multiple occasions served as a consultant to the United Nations on the mental health impact of environmental pollutants.

Neugebauer was in Rwanda for most of the fall and winter of 1997 working to evaluate a UNICEF program helping children with the emotional trauma they endured after seeing violence and genocide – an experience he said “put into perspective everything else in my life.” He has revisited the subject twice since in prestigious epidemiological journals. He has also studied mental health issues in Uganda, and has on multiple occasions served as a consultant to the United Nations on the mental health impact of environmental pollutants.

Who would have imagined, then, that the longest endeavor Neugebauer would ever be a part of happened right in the Bronx, where he was born and raised?

* * *

In the 1960s and 1970s, some 1.1 million gallons of chemicals were dumped into the Pelham Bay Landfill. These chemicals, 67 by one expert’s count, many of which were toxic, seeped into the surrounding water, soil, and air. A decade later, numerous neighborhood children developed Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, believed to be a result of the illegal dumping. Three children died before they reached their teens, and those that survived spent their childhood dealing with this terrible disease. Many still stuffer side effects from the treatment to this day.

Patricia Nonnon, one of the mothers whose child had died from the leukemia, brought a class action suit against the City of New York in 1991. Several other families soon joined her, alleging that the dumping caused their children to suffer, and that the city was to blame.

Neugebauer joined the plaintiffs as an expert witness in the early stages of the case. There’s no way he could have known at the time that it would take 22 years for the case to settle.

“It’s not only the length of time,” Neugebauer said in an interview in January of 2014, “it’s the length of not knowing the result — what the final outcome would be. We were psychologically suspended.”

* * *

Mitchel Ashley, one of the attorneys for the plaintiffs in the Pelham Bay Landfill Case, explained that epidemiology “is a horrible way to evaluate if leukemia was caused by chemicals. It is also, everybody agrees, the only way to determine that.”

Ashley’s words cut to the main issue that plagued his case and partially explained why it took 22 years to come to a conclusion– the difficulty of proving causation between the toxins that were dumped into the landfill and the cancer that followed. That word, “causation,” would lead to decades of frustrating legal battles between the families and the city, whose lawyers claimed there was no provable connection between the dump and the high incidence of leukemia.

The defense, naturally, wanted exact figures from the plaintiffs like those required in cases of workplace or industrial exposure. Those exact numbers were, both sides agreed, just about impossible to find in this case.

“Unless tests on children are uncovered in the Nazi archives or large-scale accidents or malfeasance [is] uncovered elsewhere, data in children are unlikely to ever be a significant factor in this type of scientific discussion,” explained Dr. Bruce Bernard, in an affidavit from 2008 when he joined the Pelham Bay plaintiffs as an expert toxicologist.

Lacking such experiments or the ability to indisputably prove their case, lawyers for the plaintiffs gathered a group of experts in an attempt to prove the impossible as best they could.

* * *

Neugebauer was involved in the case from almost start to finish. He first encountered Glaser, Shandell, & Blitz, the firm that initially represented the Pelham Bay plaintiffs, while being screened for jury duty in an unrelated case. The firm encouraged Neugebauer to work with them on future cases due to his background and expertise.

“They needed an epidemiologist and I was there,” he said during an interview in his office at the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in the fall of 2013.

As an epidemiologist, it was Neugebauer’s job to test whether there was a higher rate of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia among people who lived in close proximity to the toxin-filled landfill than among those who lived further away. The study he conducted, attorneys and fellow experts agreed, was the lynchpin of the entire case. As explained in a 2002 affidavit, Neugebauer based his hypotheses on two studies about the incidence of childhood leukemia near Pelham Bay conducted by the New York City Department of Health. The studies, conducted in 1988 and 1994 in response to community concerns about the dump, found no elevation in cancer rates.

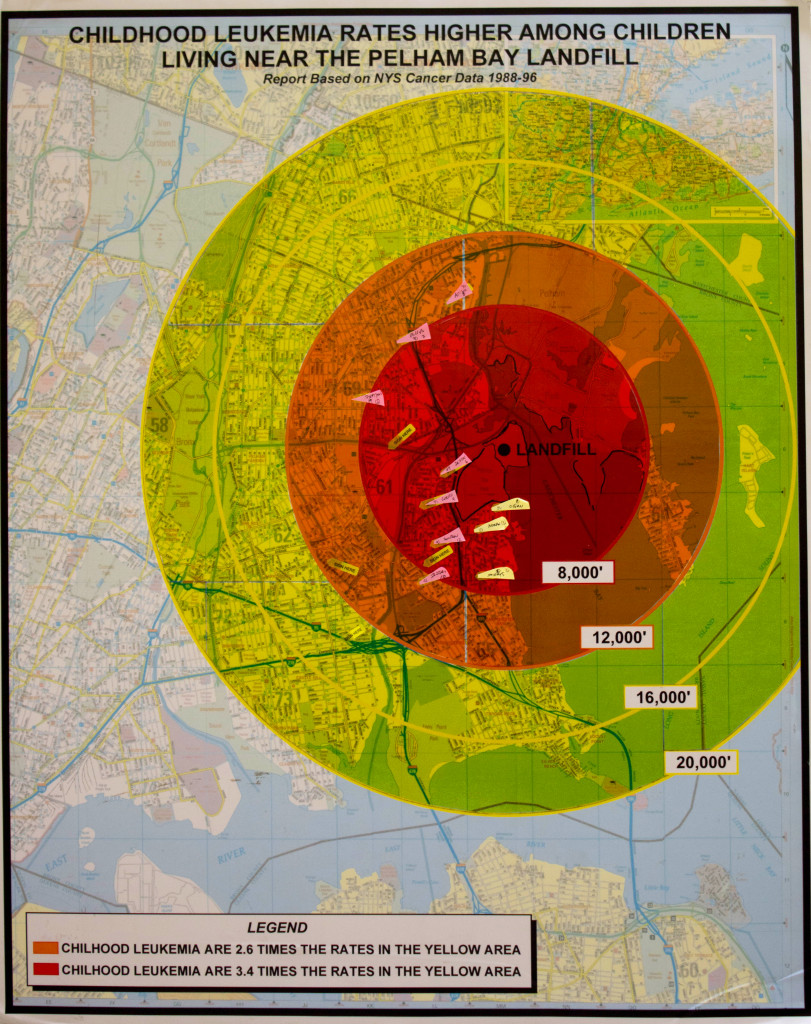

Neugebauer addressed criticism that had been leveled against these studies by two independent groups, the Pelham Bay Task Force Scientific Advisory Committee and members of the New York State Cancer Surveillance Program. These groups noted that neither study examined specific cancer subtypes such as acute lymphoid leukemia, nor did they consider data from after 1987. Using data from the New York State Cancer Registry up to 1996, Neugebauer was able to map an increase in childhood leukemia rates among those living closer to the dump. A series of circles centered on the dump divided the area into four bands. Following standard epidemiology practice the bands were measured in feet. Each was 4,000 feet wide, save for the innermost, which had a diameter of 8,000 feet as it included Pelham Bay Park and the dump itself.

From 1988 to 1996, the rate of childhood leukemia among those living in the innermost band was 3.4 times higher than those living in the outermost band. Leukemia rates in the second band were still 2.6 times higher.

* * *

Three other experts submitted affidavits in 2002. Jesse Bidanset, one of the founders of the Society of Forensic Toxicologists and former chief forensic toxicologist of the Nassau County Office of the Medical Examiner, wrote about the benzene, mercury, and other chemicals that were in the dump and said they caused the greater than usual cancer rates to a reasonable degree of toxicological certainty.

Bidanset went on to list some of the ways the city could have prevented the spread of these chemicals, including adding the use of liners or special coverings to control gas release from the landfill. He also highlighted the city’s repeated failure to act when confronted with the results of damning studies like the 1988 and 1994 ones that the city itself had commissioned.

“There was rarely any meaningful communication between New York City agencies and the study groups,” he wrote in his affidavit. “Suggested remedies were often ignored or delayed. All to the detriment of… the plaintiffs in this case.”

Dr. Diane Trainor, 63, is an ecotoxicologist and industrial hygiene expert who works for the expert witness firm Robson Forensic when she’s not teaching at Middlesex County College in New Jersey. In a phone interview in November of 2013, Trainor said she was glad that she had time off as a teacher, because the research that went into her initial affidavit back in 2001 took her “literally an entire summer.”

Using existing data from air, water, and soil pollution studies in Pelham Bay that she had compiled over the summer, Trainor analyzed the possible pathways the toxic chemicals could have taken to reach the children and make them sick. The toxins, she found, had multiple means to reach the neighborhood children. Ground and runoff waters contaminated the surroundings, and even the air, Trainor argued, was spreading cancer-causing chemicals.

“Inhalation is the most dangerous type of exposure,” Trainor wrote in her affidavit, “as the toxic chemicals go immediately into the bloodstream via the lungs.”

Dr. Philip Lanzkowsky, an expert pediatric hematologist and oncologist, would testify only that Benzene, one of the chief chemicals illegally dumped in the landfill, has been proven to cause leukemia. Lanzkowsky would not speak to causation, saying it was outside his area of expertise.

* * *

The city, not surprisingly, disagreed with the plaintiffs’ experts. Though its initial arguments were described by Neugebauer in an interview in December of 2013 as “sort of amateurish,” the city’s tactics began to improve as they gathered experts. The most notable of these was Dr. Jonathan Borak, a professor of epidemiology at Yale, who had an antagonistic relationship with the plaintiffs’ experts.

Borak heavily criticized the earlier testimony of the plaintiffs’ experts in a reply affidavit in 2003. He accused them of attacking the messenger by attempting to discredit his credentials, as Trainor, Bidanset, and Neugebauer had all made reference to Borak’s primary role as a medical doctor rather than a researcher. “Dr. Borak does not posses the correct expertise to criticize my skills,” wrote Trainor in her 2002 affidavit.

“He struck me as very, sort of intellectually insecure,” Neugebauer said in an interview in December 2013. “I’m surprised by the intensity of his feelings.”

Borak said in an affidavit the plaintiffs failed to provide any “objective measures of dose.” He was right — such exact doses are impossible to measure in environmental cases like Pelham Bay, according to multiple experts for the plaintiffs. The argument before the court was whether such doses would be required regardless.

He also leveled several criticisms against Neugebauer’s study, including a lack of explanation as to the methodology and arguing that that the study failed to adjust for the difference of age and racial distribution.

“Anything I did that they couldn’t initially understand,” Neugebauer said in the interview, “they decided that I must have done it out of deceit in an effort to make a false claim or to support this false claim.”

Neugebauer wondered in affidavits and the later interview why Borak didn’t just make the adjustments himself, since he should have had access to all the city data. In his affidavit, however, Borak said Neugebauer did not go into enough detail about how he broke down the population in the various bands of his study, and as a result Borak couldn’t recreate it.

The plaintiffs’ experts, for the most part, addressed Borak’s criticisms in the next round of affidavits. For some it was the first work they had done on the case in several years due to the tortoise-like speed of the court system. Neugebauer’s 2008 affidavit was more transparent in its methodology, and it included a lengthy section on how he arrived at his population breakdowns from the census tracts. The updated study also adjusted for age and racial distribution to counter Borak’s concerns.

With those adjustments, the relative rate of leukemia between bands was even more significant – more than four times higher in the one closest to the landfill.

* * *

During the time the plaintiffs’ experts were addressing Borak’s criticism, there would be one notable change in the makeup of the plaintiffs’ team. Bernard, an expert toxicologist and founder of the chemical consulting firm SRA International, Inc., became involved in the case after Bidanset retired to Florida.

Bernard, 68, exudes self-confidence. In an interview in November of 2013 he explained that he has two rules for himself in court. One is to teach the jury instead of telling them. The other?

“I never use the upright pronoun — ‘I,’” he explained. “It really doesn’t matter what I think. Science isn’t based on what I think.”

In Bernard’s opinion, Borak employed a lot of the “upright pronoun,” as did Bidanset on the plaintiffs’ side. Bidanset’s affidavit, he thought, took a lot for granted and did not delve deeply enough into the issues. “They were superficial. I couldn’t understand actually why in such a case it would’ve been so,” he said. He soon realized that it was “because [the case] was horrendously complicated.”

“Even if the amounts of the individual chemicals were small, they would have had a cumulative effect in terms of mutational events,” he explained in an email.

Bernard’s study therefore addressed the mutagenic potential of every chemical. He further backed-up Neugebauer’s study using the Bradford-Hill postulates – a widely accepted method for determining general plausibility of a cause and effect relationship. Created by Dr. Austin Bradford Hill in 1965, the evaluation scheme examines the association in nine ways, including the strength, consistency, and specificity of the association. To get all this done, Bernard said in the interview, he had to drop every other project and put his entire staff on Pelham Bay full time. He had just six weeks.

Bernard said he only became involved because he was asked as a favor by his friend Kenneth Morrow, an attorney with Mauro Goldberg & Lilling, a firm that represented the families when the case went before the Court of Appeals in 2007. Were it not for Morrow, who has since died, he said he never would have gotten involved due to the amount of work it was going to take to create a good, scientific case.

Bernard’s affidavit was 55 pages long. Bidanset’s was seven.

* * *

Neugebauer said in an interview that he tried to avoid spending too much time with the families because he didn’t want them to believe he was “on their side and rooting for them.” He said “scientific obligations… take precedence.”

On a personal level, Neugebauer admitted, however, he was very glad that the science led to the conclusion it did. “I don’t think I could have sat in a courtroom testifying against the cluster with the family members of the children that had died or had been ill for a very long period of time sitting in front of me. It just goes against my humanity,” he said. “I couldn’t be party to defeating the families’ efforts to be recompensed, not that they ever can be.”

Lanzkowsky, 82, the hematologist, adhered so closely to the good science doctrine as he saw it that he was potentially a liability for the plaintiffs. In his affidavit, which he described as “extremely carefully worded,” he wrote only of the effects of leukemia and the drugs on the plaintiffs, and confirmed that Benzene caused leukemia. He did not, however, speak to the link between Benzene and the specific acute lymphocytic leukemia that the children had due to the lack of data.

He also did not comment on the dump being the cause of these cancers, saying it was outside his area of expertise. “You see, I’m a physician,” he said in a recent phone interview, “so I deal with children who have leukemia. I don’t deal with the wind blowing Benzene out of the ground.”

Lanzkowsky, a good-natured South African who has practiced in New York since the 1960s, was therefore the only expert involved in the case whose testimony went largely undisputed by the defense. He wasn’t even allowed to look at Neugebauer’s study, nor was he interested in doing so. That way, he said, he couldn’t express any opinion if he was cross-examined.

* * *

Lanzkowsky never was cross-examined, and the experts never got the final chance to attempt to prove their impossible case. Though their efforts were not in vain – they had, after all, been able to convince an appellate court on three occasions that the case deserved to go to trial – there was no final showdown; as the case was settled in July of 2013 for $12 million. Attorneys have not specified how that sum will be distributed among the plaintiffs.

Neugebauer found out about the settlement while traveling from Stockholm to Helsinki on vacation. Jeff Korek, one of the plaintiffs’ attorneys attempted, unsuccessfully, to reach him. When Neugebauer tried to call him back, Korek told him that it wasn’t a problem, and that he would tell him about it when he got home.

“And then I read in the Times the following day or maybe three days later that the case had been settled,” Neugebauer said.

Neugebauer said he was somewhat relieved – partially to be spared “the withering scorn of the opposing counsel,” he would have endured had the case gone to trial. But he did admit that it would have been more satisfying to have won.

In interviews, Bernard and Trainor also expressed some relief that they would not have to deal with a trial, though Bernard admitted his first reaction was “Jesus, I spent all this time doing it, and now it disappears?”

Neugebauer, who grew up about ten blocks north of the Bronx County courthouse where the case would have been tried, thought the plaintiffs would have prevailed had they gone to trial, an opinion shared by most of the experts. Still, they were glad to see the case finally settled and were pleased the families were finally getting reimbursed for the hardship they endured.

Even Lanzkowsky, despite his lack of conviction regarding the cause of the leukemia, was happy to see the families receive some compensation.

“It’ll be helpful to them,” he said in a recent interview, “Who can object to that?”

* * *

Despite the settlement, there were still doubts among the experts as to whether it – all 22 years of it – had all been worth it.

Despite the settlement, there were still doubts among the experts as to whether it – all 22 years of it – had all been worth it.

“Occasionally I would think that, geez, Nonnon’s daughter would be in her late thirties,” Neugebauer said, sitting in his office at the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center. “In fact,” he continued, “that’s the first thing I thought of when I heard [that the case had been settled.] I thought, well, I don’t know how [Nonnon is] going to feel about this but… it’s not going to bring her daughter back.”

As the interview concluded, Neugebauer noted that he and the other consultants made a lot of money off the case while the families, who had lost so much already, waited for two decades on an uncertain result. “The only interests that it advances are the consultants – myself included – and the attorneys,” he said.

“There doesn’t seem to be any justice involved.”

* * *

Before Bernard agreed to join the case, he met with Patricia Nonnon. He asked them – in front of the slightly surprised lawyers – why she was pursuing this case. What did she hope to gain?

If she was looking to punish the city, and equated money with punishment, Bernard said in a recent interview, that was an obtainable, acceptable goal. If, on the other hand, Nonnon was “waiting for someone to come up to you and say, ‘yes, this was our fault. Yes we did this. Yes we’re sorry,’” Bernard said, “then I [didn’t] want to get involved. Because it’s never going to happen.”

The day of the settlement, the city’s lead lawyer Fay Leoussis, released a statement denying any guilt.